In 1969, Jim Henson locked a man in a box and let him die. Don’t worry, it was just for a movie. A movie that now gathers dust in the LAPD’s evidence room inside a locked crate marked “Too horrifying to watch”. How does it gather dust inside a locked crate? Good question.

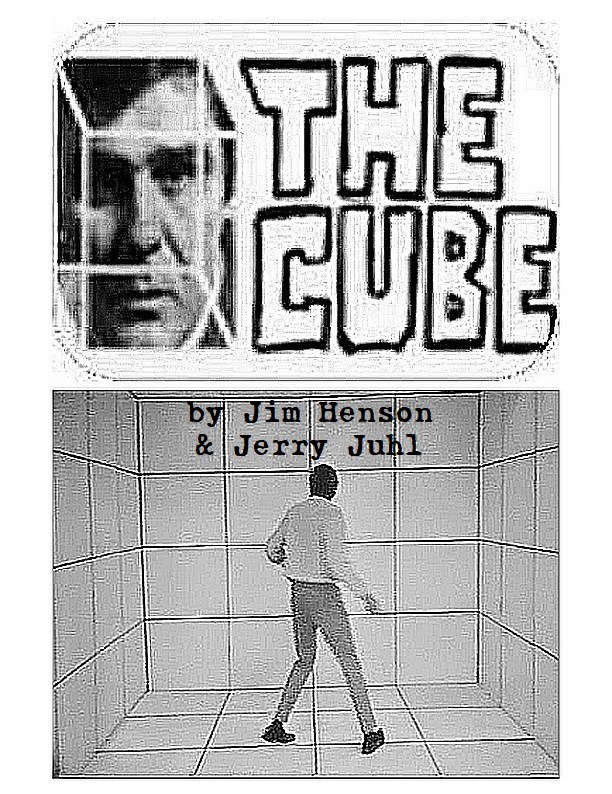

Let’s talk about The Cube, a Henson-directed telefilm from the same year.

A man is trapped in a white room. He doesn’t know how he got there, and can’t leave. People enter the room through mysterious doors (which only they can see and use), and do things to the man that might be pranks, might be torture, or might be attempts to enlighten him. They rave, threaten, lie, confabulate, explain, offer hallucinatory narratives about what’s happening, then leave. The man is still in the cube.

Henson made films about puppets. The Cube depicts a man (played by Richard Schaal) who’s metaphysically a puppet: he lacks free will, and is at the mercy of his unreliable senses. That’s the simplest reading of The Cube: we are locked inside our own minds: trapped in a skull-box, grasping at threads and slivers of light and sound spilling through pinholes and cracks and fissures, seeking meaning in the pale, languid eidolons, trying to infer the world buzzing outside the cube—a world we can never actually visit, because it would mean stepping outside the boundaries of our own awareness. We are prisoners of the sensorium. And it’s lying to us.

The 60s were a decade made for such questions. Marijuana. LSD. MKULTRA. Postmodernism. The edges of reality and perception were being tested and rewritten and overturned. Science accelerated cultural derealization: we could actually examine an eyeball, and see all the kludges and hacks holding our vision together: see the bloody lattice of veins and arteries spread across the retina, see the optical nerve which interrupts our vision (a blind spot that the brain edits out with a patchwork of surrounding data), see how the sensory sausage is made.

In 1967—one year after Henson and Muppets co-writer Jerry Juhl wrote The Cube‘s screenplay—Doreen Kimura conducted her famous dichronic experiments, revealing the mangled patchwork of the human auditory system. Simply put, aural pathways from our ears to our brain “cross over” inside our heads—what the left ear hears goes to the right side of the brain, and vice versa. But the left hemisphere is dominant for language tasks: so when human speech (for example) enters the left ear, the signal must make an additional trip from the right side to the left via the corpus callosum for processing, adding a few-millisecond delay to the sound. To compensate for this, the brain does the same thing a laggy online videogame does: by artificially delaying the signal from the right ear, so that both left and right stereo signals match. Essentially, your ears hear things happening later than they actually did. The brain coheres all this into a singular experience, a singular sound, but it’s an illusion.

The Cube could be viewed as a metaphor about scientific derealization. It also has religious readings. A Christian Scientist turned hippie, Henson likely had at least a remedial understanding of Buddhism, and The Cube kind of works as a dramatization of three “marks of existence”: Impermanence, suffering, and selflessness.

Anicca: all is impermanent. Reality inside the cube is unsettled and ill-defined. A mud that swirls into new shapes every time The Man tries to touch it Objects and people suddenly appear that weren’t there before. The words of his visitors are no more reliable: often they’re palpable lies, or contradictions. He meets a prisoner called Watson, who claims to have spent a very long time in another cube—how long, he cannot say, because when he tried to mark the passage of days on his thumbnail, they tore it out. (This itself is rugpulled: the man is later described as an actor, playing a role…which is true, of course. None of these events are happening. The Cube is a 1969 TV movie directed by Jim Henson.) There’s a layer of metafiction, as the man sees himself on a TV screen, and must process the implications.

Dukkha: all is suffering. The Man is sent reeling through psychological states. Hope, horror, amusement, confusion, sexual desire, anger. All are useless in the cube. His actions aren’t totally meaningless—people react to him, such as two clowns (the first is apparently a parody of Eddie Cantor) who become savagely angry when The Man fails to laugh at them—but he can’t escape the cube. He’s like a ball in a pinball arcade cabinet: it whips around at dizzying speed, racking up points on bumper after bumper, but will fundamentally never escape the cabinet. The cube is a hell twisted into the shape of a Kline bottle. There’s nowhere to escape, except straight back into it.

Anattā: lack of self. The Man (for he is indeed all men), is the most Hensonian of objects: a puppet. Kermit might have form and shape, but he is hollow cloth with sawed-in-half eyes. His behaviors are supplied by the ghostly demonic hand twisting inside him. Likewise, the Man has no name, and no memories. The torments he is subjected to are nonsense…but in a sense, they’re all that’s real in The Cube. A coquettish seductress walks into the cube, seems to be trying to seduce him…and then reveals it was all an act. This is cruel…but was it really fake? The lust the man felt was real. So is the anger he feels after the prank is revealed. In a sense, she has provided him with what he lacks: an identity as a lustful, angry man. Without the external world torturing him, he would just be nothing. Nothing whatsoever.

Maybe The Cube is simply a freeform Rorschach blot onto which the audience imprints their own meaning. It certainly has a hippie-esque “it’s so deep, man” vibe. And what’s the hippie term for a prisoner of the system? A square. And what’s a cube made of…?

The problem with a film about meaninglessness is that it can quickly shade into the film itself lacking meaning. The Cube does not quite reach that point, but if it had gone on longer than 60 minutes, it probably would have. The Cube is strange, challenging, but perhaps ultimately a bit shallow. Eventually, you get the idea. It’s all a weird, dark game that he’s better off not playing. Instead, even at the end he’s still basically falling for the idea that there’s some “deep reality” that he can reach beyond these shifting stands. Most of the film consists of arbitrary events, that could probably be rearranged in nearly any order with no loss of meaning.

Many of the tricks played on The Man are also tricks on the viewer. A strange monklike figure gives him a mystic artifact called a Ramadar, which might be key to his salvation. But all the Ramadar seems to do is make an annoying buzzing sound, and he smashes it in frustration. Is this a metaphor for the impossibility of enlightenment, or just another red herring? You decide.

The mind is a dark place where all of us live, yet none of us live. And certainly, it is not a place we can escape. My dad had a running joke (likely stolen from some comedian), that old TVs had dust traps down the bottom, and after you watched an old western, you had to empty out all the dead Indians from the bottom of your TV, before they started to smell. They were probably happy to go. They escaped the cube.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.